Preservation Institute

The Natural Environment : The Social Environment

Transportation and Development Politics

Political Theory: Beyond Progressive and Conservative

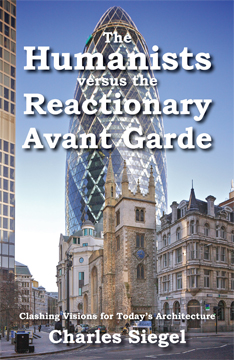

The Humanists versus

the Reactionary Avant Garde

Clashing Visions for Today's Architecture

copyright 2016 by Charles Siegel

published by Omo Press

Read a selection from the bookBuy or preview the book on amazon.com

|

"Siegel makes a clear and intelligent case, based not on romantic nostalgia but on the pressing issues of contemporary society. I recommend this book in the strongest possible terms."

- Prof. Nikos Salingaros, author of A Theory of Architecture

"Among the ... books on this topic that I have read, yours is by far the most sophisticated and the most up to date."

- Andres Duany, principal of DPZ Partners

"The Humanists Versus the Reactionary Avant Garde was sitting on a shelf in my office, awaiting review, for several weeks. I was busy, and in a chance conversation I told CNU co-founder Andres Duany that I didn't know when I would find time to read it. "You have time for this book," Duany assured me.

... author Charles Siegel clarifies the confusing world of modernism and post-modernism and connects them to New Urbanism in new ways--and he does this is a compact 162 pages. ... Whether you care about style or just want to make good places for people, the book offers useful insights--and not just about architecture.

... The Humanists confronts a vital issue: How can architecture and design address the human needs of our time? In doing so Siegel has written a gem of a book....."

—Robert Steuteville in Public Square, published by the Congress for the New Urbanism

Read the entire review

During the early twentieth century, modernist architects shared progressives' vision of a more prosperous high-tech future.

Today, we can see that we must make selective use of technology, using technologies that are beneficial and controlling those that are destructive. Beginning in the 1970s, postmodern architects were part of a larger social movement to use technology for human purposes.

But today's avant gardists have rejected this humanistic impulse and regressed to the modernists' love of technology for its own sake.

The avant gardists are conservatives, celebrating the status quo of our technological economy. Neotraditional architects are the real progressives, trying to humanize our economy.

With its new view of the history of architecture, its hilarious examples of antihuman avant gardist designs, and its inspiring examples of designs that learn from traditional models, this book will convince you that the emperors of today’s architecture have no clothes.

The Humanists versus

the Reactionary Avant Garde

by Charles Siegel

Chapter 1: Architecture and Technology

Architects in a technological society can support the status quo by glorifying technology, or they can challenge the status quo by humanizing technology.

Our avant-gardist architects claim they are progressive because their buildings are futuristic, but their work is really pure esthetics with no political content. They criticize the traditional architecture and neighborhood design of the New Urbanists as nostalgic and conservative, but many progressive environmentalists support New Urbanism.

The avant gardists are not really progressive politically because they do not engage a key political question of our time, how to use modern technology in more humane and sustainable ways. While the avant gardists produce flashy buildings that get all the media attention, the neotraditional designers are doing the hard work of designing buildings and neighborhoods that are good places for people - developing a humanistic architecture and urbanism.

Modernist Design

In the early to mid-twentieth century, architecture and urban design both were dominated by modernists who glorified technology, as we can see by looking at two famous designs.

Mies van der Rohe's glass and steel apartment buildings on Lake Shore Drive, Chicago (1949-1951) are typical examples of mid-century modernist architecture (Figure 1-1). This sort of boxy high-rise, with a steel skeleton and glass curtain walls, soon became the standard design for office buildings as well as for apartments. Our cities are now filled with variations on this theme.

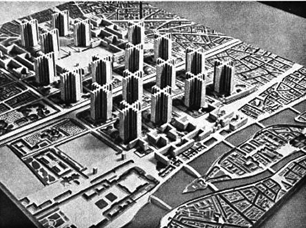

Le Corbusier's Voisin plan (1925), is a typical example of modernist urbanism. This plan would have demolished the Marais district of Paris and replaced it with identical sixty-story towers in a park-like setting (Figure 1-2). Though the Marais district was spared, many urban neighborhoods in the United States were demolished and replaced with high-rise housing projects during the 1950s and 1960s, when this style of urban renewal was popular.

Figure 1-1: Mies van der Rohe, apartment buildings on Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, 1949-1951. Mies' two buildings (in the foreground) looked striking when they were first built and stood in isolation, but they just look oppressive now that they are surrounded by other buildings in the same style. Photo by JeremyA.

Figure 1-2: Le Corbusier, Voisin Plan for Paris, 1925. This sort of tower-in-a-park slum clearance was popular in the United States in the 1950s and 1960s, when modernism was the establishment style of urban design.

Modernist design became so popular during the mid-twentieth century because these gleaming glass, steel, and concrete buildings symbolized the technological optimism of the time. This style proclaimed that the modern era was so advanced that it could ignore models from the past and redesign society on scientific grounds. Architecture helped spread the faith that, by unleashing technology, we could heal the sick, replace the slums with hygienic housing projects, and create affluence for all.

This sort of technophilia made some sense a century ago. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the average American's income was near what we now define as the poverty level, but the economy was growing quickly. Because of rapid industrialization, per capita GNP in 1900 was almost twice what it had been in 1870.1 It seemed that industrialization would make it possible for the masses to escape from poverty for the first time in history. New technologies and economic growth were overcoming scarcity and promising a better future.

This technophilia no longer makes sense today, because the economic changes of the last century have made it obsolete. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, average income was more than five times as much as it was in 1900 (after correcting for inflation). Because most Americans today have the basics and more, the promise that technology and economic growth would bring us the basics no longer seems as relevant as it did a century ago.

In 1900, middle-class Americans who lived in streetcar suburbs did not own vehicles; only the rich could afford to keep carriages in our cities and suburbs. Today, most American households own two or more cars, and there are more cars than there are licensed drivers.

In 1900, many of America's urban workers lived in crowded tenements, where there was only one toilet per floor, where you filled a tin tub in the kitchen to take a bath, where inner rooms had no sunlight, and where children had nowhere to play except the streets. The modernist designs for "workers housing" (and the mid-century housing projects built in their image) had windows that let natural light into every room, had a private bathroom for every apartment, and had lawns and playgrounds for the children. No one minded that these designs were standardized and impersonal; they provided the basics of a decent life, and this alone made them look good compared with the slums.

By the 1960s, economic growth had already allowed most Americans to escape from poverty. One economist became famous by writing in 1958 that America was an "affluent society."2 Most people already had the minimum basics of a decent life, so they were less likely to be impressed by the promise that technology would bring them the basics in the future. Workers were moving to the suburbs, and they certainly did not want to live the in drab housing projects that had looked good when modernists first proposed them at the beginning of the century.

At the same time, it became obvious that technology was creating problems, such as pollution and traffic congestion. In the 1960s there were widespread criticisms of the abuses of modern technology and calls for a new focus on the quality of life, which became a major force in American politics after the first Earth Day in 1970.

Beyond Modernism

During the 1960s and 1970s, architects and urbanists were among the leaders of this new movement focusing on quality of life, and they often criticized modernism. The modernists rejected the past in favor of the newest and flashiest technology, but critics of modernism were willing to learn from the past about how to use technology for human purposes.

By the 1960s, it was clear that the modernist urbanism was making American cities less livable. Low-income housing projects, in the style of Le Corbusier's Voisin plan, had higher crime rates than the older neighborhoods surrounding them. Freeways were blighting old urban neighborhoods. Freeway-oriented suburbs were paving over the countryside, replacing it with ugly sprawl.

Urbanists led the way in criticizing the misuse of technology in mid-century America: citizen protests against urban freeways, criticisms of urban sprawl, and the obvious failures of modernist housing projects helped to burst the bubble of mid-century technophilia. For decades, this criticism of modernism was largely negative, focused on stopping freeways, sprawl, and massive urban renewal projects, but by the 1980s, it turned positive: The New Urbanism became the most important movement in city planning, and it moved beyond modernist urban design by learning from traditional models of urbanism. The New Urbanists began building old fashioned, walkable neighborhoods again, with homes facing the sidewalks and with Main Streets that have apartments above the storefronts.

Architects also began to criticize modernism in the 1960s; and by the 1970s, it seemed that modernist architecture was being replaced by a postmodern architecture that was willing to learn from traditional models. But postmodern architecture was ambivalent. It revived earlier styles in ways that were sometimes serious and sometimes ironic. Academics today focus on the ironic side of postmodernism, but this book will argue that we should be studying its serious attempts to learn from the past.

Like the New Urbanists, the serious postmodern architects were part of the larger movement to humanize technology that began in the 1960s and 1970s.

In urbanism, the movement beyond modernism has continued. New Urbanism dominates today's city planning.

In architecture, by contrast, the establishment has rejected postmodernism and has revived modernism - but in a form that no longer has its original social meaning. Mid-century modernism was idealistic and was part of a larger progressive movement for social change. Today's modernism just gets esthetic thrills from buildings that are unconventional and sometimes grotesque, and it is not connected with any larger social movement. The mid-century modernists thought they were leading us to a better society, with prosperity for all, but no one thinks that Frank Gehry and the other avant gardists are leading us to a better society.

Today, there is a split between urbanism and architecture. In the early and mid-twentieth century, architecture and urbanism fit together perfectly, as we can see in the pictures of the tower by Mies and the Voisin plan by Le Corbusier. By contrast, today's urbanists and establishment architects have very different visions, as we can see by looking at the pictures of Celebration (Figure 1-3), which looks like a neighborhood where people live, and of a Gehry museum (Figure 1-4), which looks like an avant-garde sculpture from the 1950s.

The New Urbanists are humanists who try to create good places for people, and they look down on avant gardists who are only interested in style and in flashy effects. The avant-gardist architects are esthetes, and they look down on New Urbanists who (they say) are "nostalgic" and are designing "theme parks."

Figure 1-3: Celebration, Florida, master plan by Cooper, Robertson & Partners and Robert A. M. Stern, 1996. A walkable suburb with apartments above the stores in its shopping district. The town learns from traditional models how to create a livable place. Photo by Steve Price.

Figure 1-4: Frank Gehry, Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao, Spain, 1997. The architect designs a sculpture rather than a place. This building is the icon of today's avant gardists, who specialize in icons. Photo by MykReeve.

Today's avant-gardist architects consider themselves progressive, but they are actually reactionary: they have forgotten the lessons of the 1960s and the 1970s and have gone back to the technophilia of mid-century modernism.

Society in general has moved beyond modernism since the 1970s, largely as a result of the environmental movement. There are only two groups in today's society that celebrate technology uncritically. One is the "drill, baby, drill" wing of the Republican party, which knows that it is conservative to stick with the technophilia of the 1950s. The other is the architectural establishment, which has somehow convinced itself that it is progressive to revive the technophilia of the 1950s.

Today's avant-gardism is a reactionary style, a cliquish taste that ignores the lessons that society began to learn in the 1970s. It is retrograde esthetically, a revival of earlier modernist styles. It is retrograde politically, uncritically celebrating technology at a time in history when it is vital to limit destructive technologies.

Humanizing Technology

The recent history of architecture and urbanism is important because it involves a key issue of our time: How should we use technology for human purposes?

Among mid-century modernists, the design centered on the technology. The dogma was that the design must be an "honest expression" of modern materials and functions: the building expressed the technology. The modernists' designs were so striking that they helped spread technophilia through society.

Among the serious postmodernists and the New Urbanists, design centers on the human users. They are not against modern technology, but they are selective in their use of technology. They use modern technology in ways that help to create good places for people.

For example, modernists designed cities around the automobile. They had faith that this new technology would improve our lives. In any case, it would inevitably dominate our lives, because you can't stop progress. By the 1960s, it was becoming clear that the modernists' theories had created an ugly, environmentally destructive suburban landscape of freeways, shopping malls, and auto-dependent subdivisions.

The New Urbanists take a more reasonable view of this technology: they accommodate the automobile but do not let it dominate our lives. New Urbanist design centers on creating streets and public spaces that are attractive, comfortable places for people, and it accommodates the automobile in ways that further this goal. They emphasize that their traditional urbanism can work with any style of architecture, and they mention Tel Aviv and Miami's South Beach as examples of cities where good traditional urbanism is combined with modernist architecture, but their main goal is to create good places rather than to design an "expression" of modern technology.

Modernists also designed individual buildings around new technology: the buildings were "honest expressions" of glass, steel, and concrete. By the 1970s, it was becoming clear that these buildings were cold, sterile and overwhelming. Serious postmodernists tried to design buildings that were attractive, comfortable places for people to be.

Yet today's avant gardists have gone back to the sterile high-tech design of the modernists with added "artistic" pretentions. They often create very uncomfortable places for people to be.

The use of technology is a key issue of our time, because modern technology gives us more power and more freedom of choice than ever before, and we can use this power well or badly. Modern technology can be immensely beneficial; an obvious example is polio vaccination. And it can be immensely destructive; an obvious example is nuclear weapons. We need to use the beneficial technology and limit the destructive technology.

Technology also gives us immense freedom of choice, which we can use well or badly. For example, traditional agricultural societies had a limited variety of foods that grew locally, they prepared these foods in a few conventional ways, and they lived with the constant threat of hunger. Modern societies have a greater abundance and variety of foods. Everywhere in the world, people can choose to eat the corn that was domesticated in the Americas, the rice that was domesticated in Asia, the wheat and barley that were domesticated in the Middle East, the spices that were domesticated in the Indies, and a vast number of other foods that originated in every corner of the world. We can use this abundance to eat a more varied and healthier diet than any society in the past, or we can use it to eat a diet that is heavy on processed food and high-fructose corn syrup, the diet that has made today's Americans more obese than any society in the past.

It is easy to add similar examples. Modern technology lets us choose among a huge variety of drugs, which we can use to cure diseases or which we can abuse to feed addictions.

The same reasoning applies to architecture. Modern technology lets us choose among many different ways to build. Traditional societies were limited by the local materials and the relatively simple techniques available to them; their vernacular buildings were stylistically consistent because they did not have much choice about how to build. Today, we have a much greater choice of materials and of building methods. We can use this choice to design buildings and cities that are more livable than ever before, or to design buildings and cities that are more sterile and overwhelming than ever before.

The architecture establishment says we should build in styles that are "of our time" and that anyone who learns from traditional architecture is "nostalgic." They should learn from the more sensible attitude that we have toward food. The best restaurants use locally grown, fresh ingredients (as traditional societies did) because they produce healthier, tastier food, but no one says that these restaurants are "nostalgic" and that they should use mass-produced canned or frozen ingredients because industrial agriculture is "of our time."

When it comes to food, no one cares about this sort of precious esthetic criticism because we have very clear criteria for deciding whether food is good: taste and nutritional value. The best restaurants use some new technologies, such as sous vide cooking, but they use them because the food tastes better - not because they are "of our time."

These criteria are based on human nature. Our bodies evolved to need certain nutrients. Our tastes evolved to make us enjoy food that helped our ancestors survive during the period of evolutionary adaptation. Evolution has hard-wired these needs and preferences into human nature, and chefs work to accommodate them.

Has evolution also given us preferences about the buildings and neighborhoods that we live in? Are there aspects of human nature that architects should work to accommodate? We will look at this question in the next chapter.

Since the 1970s, the environmental movement has shown us that we must make a deliberate choice of technologies - for example, by choosing solar and wind power rather than coal to generate our electricity - but this movement focuses on limiting technologies that pose grave threats to health or to the natural environment. Architecture and urbanism could do much more. Because they design the built environment that we live in, they could help society learn how to use modern technology in ways that are in keeping with human nature.

Our reactionary avant gardists are designing the most dehumanized buildings ever built, but their approach is not inevitable. Just as mid-century-modernist architects helped spread blind faith in technology and progress, today's architects could help spread a more humanistic approach to modern technology.

Chapter 2 "Evolutionary Psychology and Building" is not included in this preview.

Chapter 3 "Beyond Modernist Urbanism" is not included in this preview.

Chapter 4: Beyond Modernist Architecture

Like modernist urbanism, modernist architecture focused on technology. The slogan "form follows function," implied that technology should be used in a way that serves some human function, but in reality, modernists were more interested in new technology and modern art than in the human beings who used their designs.

This is very obvious if you try sitting on a few modernist chairs. Some do take good advantage of new technology; for example, there are stackable chairs that are fairly comfortable, and this use of tubular steel and molded plastic can make life more convenient. But other modernist chairs are uncomfortable to sit in because they are designed primarily as sculptural objects that show off the properties of new materials and only secondarily for their function--for people to sit on them.

Postmodernists criticized this focus on technology beginning in the 1960s and 1970s. They moved beyond modernism by making use of traditional architecture, just as urbanists of the time were moving beyond modernism by making use of traditional urban design. Yet there were two sides to postmodern architecture, as we will see: one side used tradition in a serious way, trying to learn from traditional architecture how to create good places for people to be, while the other used elements of traditional architecture in an ironic way.

The serious side of postmodern architecture designed human-scale buildings, just as New Urbanism designed human-scale neighborhoods. It was clearly an advance over modernism.

Yet beginning in the 1980s, the architectural establishment rejected this new humanism and moved back to its earlier focus on technology, bringing us the flashy avant-gardist designs that are today's elite architecture. They consider themselves progressive because they are futuristic, but the avant gardists are actually reactionaries: they ignore the lessons about the human use of technology that we have learned since the 1960s, and they regress to the focus on abstract art and on new technology for its own sake that was common in early and mid-twentieth century.

The architectural establishment ignores the serious side of postmodernism and remembers its ironic side as a historical curiosity. We will look at this establishment misreading of history in next chapter.

This chapter will look at modernist architecture and its failings. Then it will correct the establishment's view of history by showing that the serious side of postmodernism had an enduring influence, both among architects and among the public.

Part of Chapter 4 is not included in this preview.

Form Follows Human Nature

Christopher Alexander is the most important theorist of humanistic postmodernism. He wrote several very influential books beginning in the 1970s and 1980s, when he was a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and he continues to write now, working with Prince Charles' foundation in London.

In his 1979 book, The Timeless Way of Building, Alexander called for a new architecture based on the common elements that are found in all vernacular and traditional architectural styles worldwide, a way of building that people are comfortable with because it fits human nature.

Alexander said that all traditional buildings were based on patterns (which Alexander uses to mean groups of rules) that gave them the quality of being alive. These patterns do not dictate all the details of a design; they generate designs that are consistent but they also allow room for variation.

For example, peasants terracing hillsides for planting follow a few simple rules, such as building the terraces along the contours of the land and spacing the terraces at certain distances from each other. As a result, the terraces are not identical but have a general resemblance. Because they all follow these simple rules, many different peasants can terrace a hillside and produce results that are consistent but varied rather than repetitive.

The same is true of the buildings of traditional villages, towns, and cities. Builders follow simple general rules for each building type, which depend on the building's function and on the materials and building techniques that are available to them. Because they follow these rules, buildings of the same type (such as houses) are not identical but do have a general family resemblance, so the entire settlement has esthetic wholeness without uniformity and monotony. Rather than being centrally planned, it unfolds organically, as new buildings are added in a piecemeal way.

Traditional patterns that produced buildings with what Alexander calls "life" - which we can call "human scale" - developed gradually on the basis of people's experience. These sorts of patterns had been the basis of most building for many millennia, but they have broken down recently, Alexander says, because they have been replaced by patterns based on the products of modern industry, such as large sheets of plate glass. We react to this loss of organic order by trying to create artificial order through centralized urban planning, mass production, and conventional zoning laws - but this does not produce the combination of consistency and variety that we find in traditional building.

Instead, Alexander says, we should consciously create patterns similar to the patterns used in traditional building, and we should test them in practice by seeing how the buildings they generate make us feel. Eventually, these patterns will become as natural to us as they were to traditional builders.

Alexander's book A Pattern Language (1977) codifies a large number of patterns that apply on a variety of different scales - from the design of a city, to the design of a building, to the design of an entranceway or window.

Alexander himself designs buildings in an ahistorical style that is based on these patterns but that avoids any specific traditional style. For example, Alexander's Upham House (Figure 4-12) is a very appealing building because its massing and detailing give it the same human-scale as traditional buildings, but the decorative detailing is not in classical style or Tudor style, or any other historic style. It almost looks as if he wanted to build a classical balustrade and cornice, but forced himself not to use the classical style.

Figure 4-11: Christopher Alexander, Upham House, Berkeley, 1992. The building has decorative detailing, but it avoids historical styles. Photo by Charles Siegel.

Alexander cares less about architectural style than he cares about the human-scale massing that his patterns generate. He has made an invaluable contribution by describing the sorts of forms that are needed for a humanistic architecture, but his stylistic details lack the meaning that comes from long usage and historical associations. Of course, his theory does not necessarily imply that we should build in this ahistorical style, since the traditional buildings created before the patterns deteriorated were built in the particular styles of their time.

Alexander's theory is similar to the New Urbanists' practice. New Urbanist codes are like Alexander's patterns, sets of rules that generate building designs that are varied but generally consistent. The New Urbanists, like Alexander, care less about architectural style than about the human-scale buildings and neighborhoods that their codes generate.

Humanistic Post-Modernism

The widespread rejection of modernism during the 1970s led some architects to begin designing in serious revival styles, such as Alan Greenberg in the United States and Quinlan Terry in England. But the modernist sentiment that "ornament is a crime" was still strong enough that far more architects worked in a style that did not actually use traditional styles but tried (like Alexander) to learn from traditional architecture how to design buildings that were good places for people to be, with a comfortable human scale and with rich textures rather than slick glass or brutal concrete.

Because it is often ignored, we will look at a number of examples of this serious postmodern style, chosen more-or-less at random.

We can see how quickly style changed by comparing Darbourne & Darke's designs for public housing in the 1960s and the 1970s. This firm Darke became famous for designing Lillington Gardens (1961 - 70) in the Pimlico area of Westminster, London (Figure 4-13), a public housing project that broke up the massive, impersonal forms of typical housing projects; but this 1960s design broke up the box into blocky modernist forms, which look brutal despite their brick facades. The next decade, the same architects designed Pershore Housing (1976 - 77), and in this 1970s design, their rejection of modernism went further: they were willing to use traditional forms such as pitched roofs, giving the project some of the appeal of the traditional vernacular architecture of English villages (Figure 4-14). Interestingly, this project was still built on a large tract of land without a street grid, like a typical 1950s housing project (or "housing estate," as they are called in England); it had postmodern architecture but still had modernist urbanism.

Figure 4-12: Darbourne & Darke, Lillington Gardens, London, 1961-70: This 1960s project tries to humanize public housing by breaking up the box into smaller elements and using richly textured materials, but its blocky forms still look brutal. Photo by Ewan Munro.

Figure 4-13: Darbourne & Darke, Pershore Housing, Pershore, Worcestershire,1976-77: By the 1970s, the same architects were willing to use more traditional forms, including pitched roofs, and they actually succeeded in humanizing the architecture of public housing.9

A similar example of residential design, but better integrated with the street grid, is Friar's Quay (1972-5) by Fielden and Mawson (Figure 4-15). The Norwich City Council partnered with a local developer to build this project on the site of a lumber yard near the historic center of their town, and it was designed in a vernacular style that fit into that context perfectly but that is distinctive because of its steeply pitched roofs.

Figure 4-14: Fieldon and Mawson, Friars Quay, Norwich, Norfolk, 1972-5. This project is designed in a vernacular style that harmonizes with its context, the historic center of an English town.

An example of office building design in this style is the Ted Weiss Federal Building (1991-94) designed by HOK, formerly Hellmuth, Obata and Kassabaum (Figures 4-16 and 4-17). This building is on Foley Square in downtown Manhattan, near New York City's most prominent courthouses, which are in neo-classical style. Though it is 32 stories high, it fits into its context by using compatible materials, by breaking up its massing as the early skyscrapers did, and by including ornamentation, though neither the building nor the ornamentation is in any specific traditional style.

This building shows how popular this sort of serious postmodernism still was in the 1990s. HOK is the largest architecture-engineering firm in the United States. It began by doing modernist designs in the orthodox style of the 1950s and 1960s. It also does buildings in the grotesque avant-gardist style that is today 's orthodoxy, such as Tokyo Telecom Center (1995). During the 1990s, it was also working in the serious postmodern style.

Figure 4-15: HOK, Ted Weiss Federal Building, New York, 1994. From the distance, you can see that the building has massing reminiscent of an office building of the early twentieth century. Notice that the massing is divided into three main vertical areas, and the central area is subdivided into three areas. Photo by Charles Siegel.

Figure 4-16: HOK, Ted Weiss Federal Building, Detail. Likewise, the detailing is not in a revival style, but it does have the rich texture and human scale of traditional architecture. Photo by Charles Siegel.11

Another typical example of this serious side of postmodern architecture is Koshland Hall on the campus of the University of California in Berkeley (Figures 4-18 and 4-19), designed by Vernon de Mars and completed in 1990. This building respects the early classical style of this campus: its early beaux-arts buildings by John Galen Howard are white granite with red tile roofs, and Koshland Hall is a white concrete with a red tile roof. It is not in a traditional style, and it has bare concrete pillars instead of classical columns with base and capital. Yet its scale and the texture of its facade show that it has learned from traditional architecture how to create the sort of place where people feel comfortable. It emphatically rejects the modernist buildings on campus, which ignore their historical context and are either slick or brutal.

Figure 4-17: Vernon de Mars, Koshland Hall, UC Berkeley, 1990: The building is not in a traditional style, but it does have the human scale of traditional architecture and it respects its context. Photo by Charles Siegel.

Figure 4-18: Koshland Hall. The detailing attempts to create the rich texture of traditional architecture without using traditional ornamentation. Photo by Charles Siegel.

This sort of design was common on many college campuses from the 1970s through the 1990s: new buildings respected their context and imitated the human scale and richness of traditional architecture without actually being in a historical style.

Neotraditionalism Today

Though this serious side of postmodernism is ignored by the architectural establishment, it has led to the two forms of neo-traditional architecture that are common today.

The first neo-traditional style of our time is what we can call eclectic traditionalism, using historic revival styles. Straight revival styles have become more common today than they were in the 1970s, largely because of the success of the New Urbanists. Many New Urbanist developments use architectural codes that require traditional styles, because this is what the market wants. This is the architecture that the avant gardists are thinking of when they look down on the New Urbanists because their architecture is a "pastiche" - and they have a point. The New Urbanists care about good urban design, but many do not care about architectural style. Because they are using traditional styles as ornament and do not take those styles seriously, the architecture sometimes does look inauthentic.

The second neo-traditional style of our time is what we can call "the break-up-the-box style," which is probably the most common style of new residential buildings today (Figure 4-20). Like many postmodern buildings we have looked at, this style tries to imitate the massing and the human scale of traditional architecture, but it avoids any traditional ornamentation. It is very common in suburban apartment complexes and urban housing developments that are designed to have the scale and some of the feel of old-fashioned urban row houses or apartment buildings.

Figure 4-19: The break-up-the-box style is common in recent housing developments. This style is heir to the serious side of post modernism, imitating the massing of traditional row houses to humanize the design of a large project. Fifty years ago, this sort of project would have been designed as towers-in-the-park. Photo by Charles Siegel.

Unfortunately, almost all contemporary architecture schools ignore traditional design, so architects who try to imitate the human scale of traditional architecture sometimes do not know its basic principles and come up with very strange designs. Their most common error is trying too hard to break up the box (Figure 4-21): they overdo it and produce cluttered designs, because they do not know that traditional architecture uses a nested hierarchy of scales, with a ratio of about three-to-one between each element and its sub-elements.

Figure 4-20: HDO Architects, Delaware Court, 2011. Someone is trying too hard to break up the modernist box. Photo by Charles Siegel.

Chapter 5: The Reactionary Avant Garde

The histories of urbanism and architecture in the last two chapters sound very similar. In both cases, modernists reject the past and create designs based on new technology, and then people react to the modernists' inhuman designs by taking a postmodern approach that is willing to learn from the past.

The serious side of postmodern architecture was part of the larger criticism of modernism that occurred across our culture beginning in the 1960s and 1970s. Jane Jacobs' criticisms of urban freeways and slum clearance, Rachel Carson's criticisms of pesticides, the shift in public taste from processed industrial food to locally grown, natural food, and many aspects of environmentalism were all part of a widespread movement to reject the modernist obsession with new technology and instead to focus on quality of life.

The serious side of postmodern architecture, tried to learn from traditional styles how to design buildings that are good places for people. But there was another side of postmodern architecture, as we will see in this chapter, which used traditional styles in an ironic, mocking way and led to today's avant gardism.

The avant gardists have moved back to modernism - to constructivism rather than to functionalism. They are more interested in showing off what can be done with new technology than they are in creating good places for the people who use the buildings.

The avant gardists consider themselves advanced and progressive because they use the latest technology - which, in our day and age, is a bit like claiming that you are progressive because you support chemical farming rather than organic farming and freeways rather than in walkable neighborhoods.

The avant-gardist movement emerged during the 1980s, at the same time that the Reagan administration was shifting the nation to the right. Like the Reagan Republicans, the avant gardists of the 1980s were retreating from the social concerns of the 1960s and 1970s and trying to revive the spirit of the early and mid-twentieth century. Unlike the Reagan Republicans, they believed they were progressive and did not realize that they were retrograde.

They are something new in the history of art: a reactionary avant garde.

Parts of Chapter 5 are not included in this preview.

Avant-Gardist Architecture

The avant gardists' theoretical goal is to subvert conventional ideas about building. Their practical goal is to attract attention to themselves with buildings that are shockingly new and different. Both goals make them design buildings that are disorienting and uncomfortable places to be.

The members of this school are the best known architects of our time, called "starchitects" because their sensationalistic designs attract so much attention from the mass media. Their fame shows that the media is attracted to flashy novelties and cares very little about substance.

Peter Eisenman

A leading theorist of this school is Peter Eisenman. His Wexner Center (Figure 5-4), an art center at Ohio State University, is based on shifted grids that collide with each other, like many of Eisenman's buildings. Traditional buildings are based on a single grid, which means that all the walls are parallel and perpendicular to each other. By basing the walls of rooms on grids that are not parallel to each other, Eisenman creates an artsy cubist composition at the expense of disorienting the people using the building, who expect a traditional layout.

Wexner Center has some forms that recall the old armory that was once on the site, but these traditional forms are broken up so you only see fragments of them, mocking the solid feel of the old masonry building. And Wexner Center has a famous column that hangs from the ceiling but does not reach the floor, mocking the traditional notion of what a column is.

Figure 5-4: Peter Eisenman, Wexner Center, Columbus, Ohio, 1989. The broken fragments of traditional masonry forms clash with the modernist elements of the design. Inside, a column hangs from the ceiling and does not reach the floor. This sort of trick passes as profound and "subversive" in today's intellectual climate. Photo by Mike Evteev.

This building is on the borderline between postmodernism and today's avant gardism. Like ironic postmodernists, it uses fragments of traditional forms, and like the avant gardists, it uses a distorted version of the traditional building envelope.

Eisenman first became famous for writing obscure theoretical articles about what he called "deconstructivism." Just as the then-fashionable critical theory of decon-structionism tried to undermine the meanings of literary texts, architectural deconstructivism tried to undermine the meanings of architectural forms, such as columns. Deconstructivism became influential after New York's Museum of Modern Art had a 1988 exhibit entitled Deconstructivist Architecture.

The Wexner Center opened in 1989, soon after this exhibit, and the New York Times architecture critic praised the building, calling it "one of the most eagerly awaited architectural events of the last decade." But a New York Times art critic felt very differently when he reviewed the first exhibit shown there; he called the building "a spectacular failure as a place to see paintings and sculptures" because "A visitor must constantly decide where displays begin and end, what is the preferred route from one section of the exhibition to another, and where to stand for a decent look at a given work." As usual, the architecture critics love the disorienting avant-gardist design, but the people who actually want to use the building hate it.46

Apart from the deliberate attempt to disorient users, there were a couple of other flaws in the Wexner Center's design: the skylight leaked, and the glass walls let in enough light to damage the art works. At first, the museum tried makeshift solutions to these problems, covering the skylight with a membrane and the glass walls with curtains, but then they decided that the building needed a complete overhaul. Just a decade after it was completed, they closed this avant-gardist icon for three years to do a $15.8 million renovation.

Frank Gehry

The best known architect in the avant-gardist school is Frank Gehry, who has become such a celebrity that he was featured on "The Simpsons" television show.

Gehry became famous for designing the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao (1997), which looks like an abstract sculpture in the avant garde style of the 1920s or 1950s (see Figure 1-4). This building was obviously influenced by deconstructivism: it distorts the building envelop by using non-rectangular shapes, and it disorients its users because its exterior is not made up of horizontal or vertical surfaces like traditional buildings. It is clad in titanium - a material that is not very practical because of its cost but that is definitely very new, very different, and very shiny.

After Gehry did a few buildings in this style, they no longer seemed quite as new and different as they used to, and Gehry branched out by designing the Stata Center at MIT (Figure 5-5), with walls that look like they are collapsing.

Figure 5-5: Frank Gehry, Stata Center, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2004. Even more than in Gehry's earlier buildings, the desire to be new and different inconveniences and disorients the building's users. Photo by Tjeerd Wiersma.

Because the leaning walls meet the roof at odd angles, the Stata Center had so many leaks and other structural problems that that a Boston Globe columnist called it a "$300 million fixer-upper." The leaning walls disorient users by making it seem like the floors and ceilings slope, though they actually do not. MIT professor Noam Chomsky said that, when he moved into his office in this building, he got vertigo whenever he looked up at the corner where the wall met the ceiling. He almost fainted the first time he used the office, and he finally made it tolerable by filling it with plants to hide the room's shape. Chomsky also said that it was hard for him to do his work in this office because he could not hang a blackboard on a leaning wall.47

Though they have no deliberate symbolic content, Gehry's buildings inadvertently symbolize the fact that our society is devoted to sensationalism and to novelty, no matter what the expense in human terms.

Avant Gardists at Work

Daniel Libeskind might be the second most famous of the avant-gardist architects. His extension of the Denver Art Museum (Figure 5-6) has tilted walls and ceilings, which form sharp angles jutting out in many directions, and much of it is clad in titanium, like Gehry's Guggenheim museum. The building is made up of twenty planes, and none is parallel or perpendicular to another.

When it opened, Christopher Hawthorne, architecture critic for the Los Angeles Times, said that the building made him dizzy and wrote "It's a really stunning piece of architectural sculpture," but the "aggressive forms" make it "a pretty terrible place for showing and looking at art."48 Likewise, a local artist wrote a letter to the Denver Post saying that the sloping walls of the galleries made him physically sick: "After less than two minutes … I had to leave. Art is visual, and the visual disorientation of the walls made me so nauseated and dizzy I could not enjoy the fabulous art, no matter how hard I tried." The director of the museum responded to this letter and did not deny that the building caused feelings of vertigo; instead, he said "Those are what great architectural spaces do to you."49

Figure 5-6: Daniel Libeskind, Frederic C. Hamilton Building of the Denver Art Museum, 2006. Notice that the building and the sculpture in front of it are interchangeable: you could design an avant-gardist building the same shape as the sculpture or an avant-gardist sculpture the same shape as the building. Photo by Trueshow111.

We have seen a few examples of the disorienting buildings the avant gardists design, and now we will look at an example of the bleak public spaces they design. When the Pritzker-Prize-winning architect, Thom Mayne, designed the new Federal Building in San Francisco, all the talk was about the "strikingly original" architecture silhouetted on the skyline, but in reality, the most striking thing about this building is the bleakness of its public space (Figure 5-7). When there is even a light breeze, this corner is filled with a whirlwind of dust, newspapers, and plastic bags. This is one case where a video would be better than a photo, because the photo gives you some idea of how dusty the space is but does not show how the wind blows the dust and trash around in circles.

Figure 5-7: Thom Mayne, San Francisco Federal Building, 2007. A strikingly original way to create a bleak, unloved urban place. Photo by Charles Siegel.

A few years after the building opened, the local newspaper reported that this space had become a magnet for the homeless. The initial promotional material for the building said that it was "offering much-needed open space and services to the local community." But a local community resident says something very different about this space: "What you see there all day, 24/7, is people drinking, you see people urinating on the walls, you see everything." When you design this sort of bleak space, it is not surprising that the only people who are attracted to it are those who have no better choice. It is no more surprising to find homeless people here than to find them camping under a freeway overpass. The only thing that is surprising is that anyone ever took seriously the architect's claim that this space would become a hub for improving the neighborhood; apparently, they believed in the Pritzker Prize rather than believing their own eyes.

We have looked at examples of the starchitects' most extreme work, which disorients and even sickens the buildings' users. We should add that most of the starchitects' buildings just add artsy veneers to more-or-less conventional buildings. For example, Norman Foster's "Gherkin" in London (Figure 5-8) feels pretty much like any modern office building to the people who work in it. The building is just as sterile, impersonal and overwhelming as the boxy office buildings of the 1960s, but the artsy design has made it more acceptable to build corporate offices that damage London's traditional human scale. Far from being "subversive" rebels, starchitects are defenders of the corporate status quo.

Figure 5-8: Norman Foster and Arup Group, 30 St Mary Axe, London, 2003 (known as "The Gherkin"). The artsy design helps to justify another impersonal blockbuster office building, which clashes with London's traditional human-scale urban fabric. Photo by Aurelien Guichard.

A Parable

It would be monotonous to keep describing the foibles of our celebrity avant-gardist architects. They all have the same goal - being new and different, even if the building is uncomfortable and disorienting to its users. They all design buildings as abstract sculptural objects and as intellectual games, rather than designing good places for people.

Instead of making these same points about each of the avant gardists, we can sum up their approach by looking at the story of one of Peter Eisenman's early commissions.

In the late 1960s, Eisenman was known for his fiercely polemical and hard-to-read architectural manifestos, but he had only built one project, an addition to a house in Princeton that he called House I. He met Richard and Florence Falk at a cocktail party in Princeton, and they were so fascinated by his dense architectural theorizing that they hired him to design a house on a farm that they had purchased in Vermont, which he called House II. Richard Falk recalled in a later interview that, when Eisenman talked to him about a Chomskyesque house, "I don't know what it meant, but it sounded good."

When the Falks returned to their Vermont farm after a sabbatical, they found a house that was not yet complete but that would obviously be totally unusable. It had a flat roof, which was not practical in Vermont's heavy snow. It had a series of openings in the upper floors, which were meant to let light penetrate but which were also dangerous for the Falk's one-year-old son. It had hardly any interior walls: there were just half walls between the bedrooms. Because there were not complete walls, even a whisper could be heard through the entire house, and the Falk's son was not able to play inside during his entire childhood because his parents needed quiet to work.

The Falks were able to make the house usable by doing a major remodeling that included adding walls. Ms. Falk commented that Eisenman's design "was all about space, the eye moving with nothing to stop it" - which meant, she added, that it impressed visitors but was very hard to live in.

Three decades later, Eisenman responded to the Falk's criticisms of his house: "I don't design houses with the nuclear family idea because I don't believe in it as a concept. I was interested in doing architecture, not in solving the Falks' privacy problems."50 When Eisenman talks about "doing architecture," he obviously means designing buildings for the cognoscenti who are interested in abstract art and obscure theoretical issues. He does not mean designing buildings that are good places for the people who use them.

A parable can help us understand why starchitecture is so inhuman. Once upon a time, there was a tailor who became famous by writing hard-to-read essays about sartorial theory, though he had never actually made any clothing except one suit for himself. Finally, his fame attracted a customer, and the tailor created a suit that was in keeping with his decontructivist theory of clothing design. When the customer put on the suit, he found that it had an arm where the left leg should be, which made it painful to walk; it had a leg where the right arm should be, which made it difficult to use his right hand; and it had two arms coming out of random locations in the back of the suit jacket. The avant-gardist critics all said the design was brilliantly subversive of conventional ideas about what a suit should be. When the customer had the suit altered so he could walk around without pain, the tailor was furious and said, "I was interested in doing clothing design, not in solving his mobility problems."

At the end of the parable, we learn that this tailor obviously attracted very few customers and could not support himself designing such of uncomfortable clothing. He was forced to change his occupation, and he ended up doing honest work by getting a job as a taxi driver.

The difference is that tailors sell suits to the people who wear them, while architects often sell buildings to people who rarely use them. In particular, the trustees of museums and other cultural institutions enter the buildings only on occasion, and they do not have to live with the buildings' avant-gardist designs. Museum trustees also tend to have more money than knowledge, so they are easily impressed by the obscure theories of avant-gardist critics. The staffs of these cultural institutions do have to live with the buildings, but they tend to be so artsy that they are among the few who are eager to suffer in a building acclaimed by the critics. This is why so many of our famous avant-gardist buildings are museums and other institutions dedicated to what now passes as high culture.

A Throwback

The New York Times' former architecture critic, Nicolai Ouroussoff, inadvertently admitted that his avant-gardism is a throwback when the Times called him back to write an obituary for Oscar Niemeyer.

Ouroussoff was notorious, when he was New York Times architecture critic, for focusing most of his articles on a small number of avant-gardist starchitects. He was the leading advocate of this style.

Niemeyer was notorious for his work on Brasilia (Figure 5-9), the new capital city that Brazil built between 1956 and 1960. Lucio Costa did the general plan, after winning a competition in 1956, and Niemeyer was the chief architect and designed the government buildings. Niemeyer had worked with Le Corbusier on the United Nations headquarters, and he said he was influenced by Le Corbusier. This influence is very obvious in Brasilia, and you can see in the illustration that Brasilia makes all the errors that have made today's city planners reject modernism. Wide arterial streets separate the government buildings in the center from the housing next to it, like a textbook example of how to make cities that do not work for pedestrians. The housing is in rows of identical high-rise slabs, like a textbook example of how to create sterile, lifeless housing projects. The government buildings face a large park-like space that is empty and devoid of life.

The city is designed as a work of abstract art rather than as a good place for people to live, and Ouroussoff loves that artsy design. He says of Niemeyer's government buildings, "His curvaceous, lyrical, hedonistic forms helped shape a distinct national architecture and a modern identity for Brazil." If you were a hedonist, would you want to live here? Ouroussoff is speaking as a disembodied esthete who enjoys contemplating Brasilia's design from a distance, and he does not care about what it is like to live there.

Oscar Niemeyer, principal architect, and Lucio Costa, principal planner, Brasilia, 1956-60. If you were a hedonist, would you rather live here or in Paris? Photo by Heitor Carvalho Jorge.

Most astounding, Ouroussoff admits in this article that his own view is actually a throwback to the modernism of the 1950s.

A decade or two after it was built, Brasilia was known as a model of everything that is wrong with modernist design. As Ouroussoff says:

"Modernism was by then falling out of favor with the architectural establishment. Brasília soon became a symbol of Modernism's failure to deliver on its utopian promises. The vast empty plazas seemed to sum up the social alienation of modern society; surrounded by slums, the monumental government buildings of its center exemplified Brazil's deeply rooted social inequalities."51

But beginning in the 1980s, the avant gardists whom Ouroussoff loves began to admire Brasilia again, as he says:

"... a growing number of people had begun to re-examine the legacy of postwar Modernism and appreciate his [Niemeyer's] purist vision as a throwback to a more optimistic time."

Though he considers himself progressive, Ouroussoff actually admited, at this unguarded moment, that people who think like him are throwbacks, nostalgic for the technological optimism of mid-century.

But we are not going to solve the problems of the twenty-first century by reviving the technophilia of the 1950s. Today, we have reached the point where we need to limit destructive effects of technology, rather than blinding ourselves to them. For example, city planners today recognize that we need a walkable street grid to connect business districts with nearby housing, in order to conserve energy and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Ouroussoff ignores this point completely: he is nostalgic for an automobile-oriented 1950s design.

No serious urbanist would admire Brasilia, because urbanists have learned from the failures of modernism. But avant gardists have begun to admire Brasilia again, because they are reactionaries who want to revive the spirit of mid-century modernism.

Ouroussoff showed his reactionary bent even more clearly in an earlier column, written just after the death of Jane Jacobs, where he criticized her because "she never understood cities like Los Angeles, whose beauty stems from the heroic scale of its freeways ...."52 It is hard to believe that he could criticize Jane Jacobs for appreciating walkable cities rather than freeway-oriented cities at a time when global warming had already begun and when the automobile was the largest source of greenhouse gases in California. They know better in Los Angeles itself: when Ouroussoff wrote this, Mayor Villaraigosa was supporting smart growth, with dense housing around transit stations, to change Los Angeles from a freeway-oriented to a pedestrian and transit-oriented city, and just two years later, California passed SB375 requiring that all of its cities plan for smart growth to help control global warming.

When Ouroussoff talks about the beauty of cities built around freeways, this spokesman for the avant gardists shows that he does not have a clue about the political issues that are important to progressives today.

He thinks of cities as aesthetic objects, and he looks down his nose at anyone who doesn't share his cliquish taste for the "beauty" of cities built around freeways - but his aesthetic is so retrograde that he does not have anything to be snobbish about. He wants to move backward in history - to ignore global warming, to ignore smart growth, to ignore the freeway revolts of the 1960s, and to go back to the "technological optimism" of Robert Moses and Sigfried Giedion. His comment about the "heroic scale" of the freeway echoes Giedion's talk about the "great scale" of the freeway.

This sort of thinking was understandable when Giedion wrote in 1941, but today we have had much more experience with urban freeways, and we know much more about global warming. When we hear someone who still advocates this sort of mid-century urbanism, we can only roll our eyes and think "how can anyone be so reactionary?"

Chapters 6, 7, 8, and 9 are not included in this preview

Footnotes are not included in this preview