Removing Freeways - Restoring Cities

Produced by the

Preservation Institute

Introduction:

Tear It Down!

by John Norquist

Portland, OR:

Harbor Drive

San Francisco, CA:

Embarcadero Freeway

San Francisco, CA:

Central Freeway

Milwaukee, WI:

Park East Freeway

Toronto, Ontario: Gardiner Expressway

New York, NY:

West Side Highway

Niagara Falls, NY:

Robert Moses Parkway

Paris, France:

Pompidou Expressway

Seoul, South Korea

Cheonggye Freeway

Freeway Removal

Plans and Proposals

Conclusion:

From Induced Demand

to Reduced Demand

by Charles Siegel

Portland, OR

Harbor Drive

During the 1960s, Portland was a city with serious economic and environmental problems.

Today, Portland is an economic and environmental success story. It is so successful that the Wall Street Journal, which is not usually known for its environmental advocacy, has called Portland an “urban mecca” that city planners from all over the country visit to learn how they can control sprawl, reduce automobile dependency, and build lively and attractive pedestrian-oriented neighborhoods.

When Portland decided to tear down the Harbor Drive freeway, the city made one of key decisions that transformed it into a national model for effective city planning.

Transforming Portland

During the 1960’s, downtown Portland’s downtown was declining, like the downtowns of many other American cities, even though its first high-rise office buildings had appeared.

The housing supply in downtown declined drastically: between 1940 and 1970, the number of housing units in downtown dropped by 56 percent, as homes were demolished to build an urban renewal project and the Stadium Freeway (I-405).

Retail business in downtown also declined drastically after the Lloyd Center (a suburban-style shopping mall in a neighborhood just a few miles from downtown) opened in 1960, and business kept declining as more malls opened in suburban Washington and Clackamas counties. Downtown had few restaurants or events that attracted people to downtown in the evening.

To top it off, the city’s air pollution was so bad that the daily fines levied by the newly established Environmental Protection Agency threatened to bankrupt the city.

Between 1970 and 1980, Portland made a number of decisions that transformed the city by moving from automobile-oriented development to pedestrian and transit oriented development. The most important were:

-

Pioneer Square: In January, 1970 the Portland City Planning Commission voted to deny a permit to build a 12 story parking structure on Pioneer Courthouse Square. The site had been occupied by a two-story parking structure, and it is now an attractive, pedestrian oriented plaza.

- Harbor Drive: In May, 1974, the state of Oregon closed Harbor Drive so it could use the land to build Tom McCall Waterfront Park, which would open up the waterfront to pedestrians, creating an important amenity for downtown.

-

Mount Hood Freeway: In summer, 1974, the Portland City Council killed the Mount Hood Freeway and instead used the freeway’s federal funding to build the downtown transit mall, eastside light rail, and other transit projects. This freeway was part of a plan to criss-cross Portland with freeways, drawn up by Robert Moses, and killing it also killed all the freeways that were to follow.

-

Comprehensive Land Use Plan: On October 16, 1980, the City Council adopted the Portland Comprehensive Land Use Plan, which established an urban growth boundary to stop sprawl and concentrated new development around public transportation stops.

The comprehensive plan is best known of these decisions. But tearing down Harbor Drive and replacing it with Tom McCall Waterfront Park was also a key step in transforming Portland from a freeway-oriented city to a pedestrian oriented city.

Portland’s Traffic Engineers at Work

During the mid twentieth century, traffic engineers sliced freeways through Portland, as they did in other American cities.

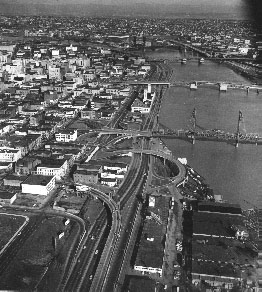

In 1942, Harbor Drive was completed. It was a four-lane freeway along the west bank of the Willamette river, which cut off pedestrian access from downtown to the river. This public works project, funded by the Roosevelt Administration to stimulate the economy, was called an expressway and was not built to modern freeway standards, but the illustration shows that it did meet the usual definition of a freeway: it was a limited access road, closed to pedestrians and to cross traffic, with access through freeway interchanges.

Harbor Drive in about 1964.

In 1968, the Journal Building (top center,

between

the

two bridges) was

acquired

by

the city of Portland,

which

wanted

to demolish it and use the

land to expand

the

freeway.

In 1960, the state completed the Portland/Vancouver Metropolitan Area Transportation Study, which proposed building 50 new freeway projects by 1990. As in other cities, the freeway system planned in the early 1960s was so extensive that it would have sliced up the metropolitan area beyond recognition. As in other cities, most of the proposed freeways were stopped because of lack of funding and because of the citizen’s freeway revolts of the the 1960s and 1970s.

In 1964, the state completed the first freeway proposed under this plan, I-5, sometimes called the Minnesota Freeway, along the east bank of the Willamette River. Now, the public had lost access to both the west and east bank of the river.

In 1968, the State Highway Department proposed widening Harbor Drive, and the city of Portland acquired the Journal Building to provide more land for the right of way.

Tearing Down Harbor Drive

By this time, many people in Portland had other ideas about how cities should be designed. They were ready to revive the ideas that were first introduced in a 1903 study by Frederick Law Olmsted that called for parks within the city and greenways along the riverbanks.

In 1968, the city’s Downtown Waterfront Plan recommended eliminating Harbor Drive and developing the land as a park to beautify the downtown riverfront.

In July, 1969, Allison and Robert Belcher and James Howell formed the group Riverfront for People, to fight against the expected widening of Harbor Drive. In addition to campaigning through the press and petition drives, the group held picnics on the site, next to the Journal Building, to attract public attention to the issue.

In August, 1969, the Portland City Club issued the report "Journal Building Site Use and Riverfront Development," which recommended that the riverfront should be developed to provide 'varied public use of land; esthetically pleasing environment; and easy and attractive pedestrian access...'

On August 19 1969, because of the citizen outcry, Governor McCall instructed the Intergovernmental Task Force working on the issue to hold a public hearing on the future of Harbor Drive. The Task Force drafted three options:

-

The original plan to widen Harbor Drive to six lanes in its current location, and straighten it.

-

A cut and cover plan, which would underground Harbor Drive and build a park above it.

-

A plan to widen Harbor Drive to six lanes and relocate it to Front Avenue, a block further from the riverfront.

Because of the traffic engineers’ objections, the Task Force did not even consider the option of closing Harbor Drive. State Highway Engineer Forrest Cooper said that would be totally impossible, because his projections showed there would be 90,000 trips per day in the corridor by 1990.

On October 14, 1969, the Task Force held the hearing, which lasted an entire day. The headline in the Portland Oregonian the next day neatly summarized the testimony: "Speakers Criticize Proposals of Waterfront Development Task Force."

Glenn Jackson, Chair of the Task Force, promised that the public’s input would be taken into consideration before any final decision was made, and he admitted that the public clearly wanted to consider the possibility of completely eliminating Harbor Drive, wanted the state to hire independent professional consultants to work out a plan, and wanted the state to work more closely with the public.

In November, 1969, as a result of this hearing, Governor McCall urged that a citizen’s advisory committee be appointed to help plan the project.

In December 1969 the 18 member citizens' committee held its first meeting, and it hired the independent consulting firm DeLeuw Cather & Company, San Francisco, to study Harbor Drive options.

Once again, the traffic engineers said it was impossible to convert Harbor Drive to a park. DeLeuw-Cather recommended creating a couplet of two wide one-way streets to carry the Harbor Drive traffic: Harbor Drive would be replaced by a surface street carrying traffic in one direction, and Front Avenue (the next street up from Harbor Drive) would be made one-way to carry traffic in the other direction.

Richard Ivey, a planning consultant based in Portland, disagreed with the DeLeuw-Cather recommendation. He argued that Front Avenue alone could carry the traffic if it had better traffic lights, a median, and repaving that would support truck traffic.

Glenn Jackson, chair of the Governor’s Task Force, was under pressure from Governor McCall to kill the DeLeuw-Cather Plan and replace Harbor Drive with a park. McCall was a steadfast environmentalist: two years before being elected, he had produced a documentary about the health of the Willamette River named Pollution in Paradise, and one of his goals as governor was to give the public more access to the river.

On the day Jackson had to present a plan to the Portland City Council, he called Ivey to his office. He told Ivey that Portland Traffic Engineer Don Bergstrom was saying that closing Harbor Drive would back traffic up all the way to Lake Oswego. He showed Ivey an editorial in that day’s Oregonian saying that it was impossible to close Harbor Drive, because the traffic engineers in Salem and Portland said it would not work. Then he shrugged and said he wanted to close the freeway: “Hell, all I’m trying to do is help the Governor. My boys tell me that you can’t close it. What are we going to do?”

Jackson talked to Ivey for three hours, and then he had Ivey’s plan for the road drawn up by the state’s engineers. He presented the City Council with this plan and with Ivey’s theory that, if the public was notified about the closure in advance, traffic would simply be diverted from Harbor Drive to parallel freeways with extra capacity. The council was convinced.

The state began closing portions of Harbor Drive on May 23, 1974, after the Fremont Bridge would be completed to carry traffic to parallel roads. By the end of 1974, the entire road was closed and development of the park began. This park opened in 1978 and was renamed Tom McCall Waterfront Park in 1984.

On the day Harbor Drive closed to through traffic, Ivey happened to run into Portland Traffic Engineer Don Bergstrom, who had said that closing the freeway was impossible. Bergstron greeted Ivey by saying, “Well, Dick, you must be a mighty proud fellow today.” Ivey asked why he should be proud: he had gone on to other things, and he was not even following the issue any longer. Bergstrom explained, “They closed Harbor Drive today and there wasn’t a ripple.”

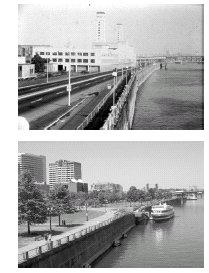

Above: the waterfront

in the 1960s,

with Harbor Drive

cutting off public access.

Below: the same waterfront

in

the 1970s, after

Harbor Drive was replaced

by a park.

Revitalizing Downtown Portland

Today, McCall Waterfront Park is an attraction that draws people to downtown Portland year round – and particularly during the summer, when it hosts the Rose Festival Fun Center, the Bite, the Portland Blues Festival, and largest Beer Brewers' Festival in the United States.

It has been expanded several times. During the 1980s, the city built a Waterfront Park Extension from the Hawthorne Bridge to Montgomery Street. During the 1990s, the city built the award-winning South Waterfront Park, completing a two-mile long greenway along the river.

The park has also been an anchor for new development. During the 1980s, Portland sponsored competetion to redevelop the area next to the park as what was called the RiverFront Project. The first phase, completed in 1985, included 298 housing units, an 84-room hotel, two restaurants, and a marina. The second phase, completed in 1995 added 182 townhouse units, an athletic club, and 2000 square feet of retail and restaurant space.

The RiverPlace project

is the cluster of midrise

buildings

at center left.

Downtown

Portland

is in the background.

In addition to this development that is directly linked to Waterfront Park, there is no doubt that replacing the freeway with this park contributed to the overall revitalization of downtown, which is an easy walk from the park and river now that Harbor Drive is no longer in the way.

Just as important, the fight to remove the Harbor Drive helped inspire Portland’s next battle against a freeway. In 1991, after the Oregon Department of Transportation proposed a freeway named the Western Bypass in suburban Washington county, 1000 Friends of Oregon developed an alternative plan to build new light-rail and bus service with transit-oriented development clustered around the transit stations. This battle not only convinced Portland to kill the Western Bypass freeway; it also convinced the city to adopt the regional master plan that is now a national model.

Now Riverfront for People, the same group that led the fight to remove Harbor Drive, is at it again. They now are promoting a plan to remove Interstate-5 from the east side of the Willamette River, to stimulate its development as an attractive pedestrian-oriented neighborhod, just as removing Harbor Drive from the west side of the river stimulated the development of the RiverFront project and of all of downtown.

Text copyright 2007 by the Preservation Institute

Picture of RiverFront project courtesy of Bruce Forster

Much of this information, including quotations and pictures, comes from http://pdxplan.org,

a site that

no longer

exists

but that was maitained by Ernie Bonner, Portland's former Planning Director, before his death in 2004.