Removing Freeways - Restoring Cities

Produced by the

Preservation Institute

Introduction:

Tear It Down!

by John Norquist

San Francisco, CA:

Embarcadero Freeway

San Francisco, CA:

Central Freeway

Milwaukee, WI:

Park East Freeway

Toronto, Ontario: Gardiner Expressway

New York, NY:

West Side Highway

Niagara Falls, NY:

Robert Moses Parkway

Paris, France:

Pompidou Expressway

Seoul, South Korea

Cheonggye Freeway

Freeway Removal

Plans and Proposals

Conclusion:

From Induced Demand

to Reduced Demand

by Charles Siegel

New York, NY

West Side Highway

New York’s West Side Highway was the first elevated highway to be built, with construction beginning in the 1920s. And it was the first elevated highway to collapse, decaying so badly that it had to be closed permanently in the 1970s.

When the West Side Highway was closed in 1973, 53 percent of the traffic that had used this highway disappeared, dramatic proof that building freeways generates traffic and that removing freeways reduces traffic. Yet there was tremendous pressure to replace this highway with a bigger and better freeway named Westway.

The plan was defeated after a David versus Goliath struggle that lasted for more than a decade, with a group of west-side residents, community boards, and environmentalists fighting the entire New York political establishment, including New York city’s mayor and New York state’s governor and two senators.

Now, there is a park, pedestrian promenade, and bicycle path along the Hudson River on Manhattan’s west side - public places that are real amenities for Manhattan on land that used to be blighted by an elevated freeway.

West Side Highway Construction and Collapse

The West Side Highway, officially named the Miller Elevated Highway in honor of former Manhattan Borough President Julius Miller, was part of the system of freeways created by New York’s master builder Robert Moses.

The stretch between Canal St. and 72nd St. was built between 1929 and 1936, connecting at 72nd St. with Moses’s Henry Hudson Parkway. Beginning in 1938, the highway was extended south of Canal St. to connect with the Battery, but construction of this stretch was interrupted by World War II and was not completed until 1948. Finally, in 1950, the highway was connected with the new Brooklyn Battery Tunnel.

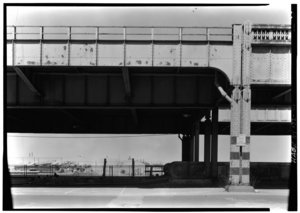

West Side Highway at Duane

St. The section above Duane St. was

built

before World

War II. The section below

Duane

St.

(to the

left) was built after

World

War II

using a

different method

of construction.

West St. at Duane St. today.

The

same

location as the

previous

picture

now that the highway has

been removed.

When the first stretch of this highway was completed, the New York Times marvelled that "the gleaming new concrete ribbon" would let drivers travel from lower Manhattan “nearly to Poughkeepsie without having to stop for a traffic light or slow up for an intersection.” Moses promised that it would “eliminate” congestion on Manhattan’s west side.

Because it was the world’s first elevated highway, there were no design standards when it was built, and in retrospect, its design seems unsafe because of its sharp curves and its narrow lanes and entrance ramps.

A 1957 study by the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority (controlled by Robert Moses) recommended realigning the highway’s curves and widening its entrance ramps. A 1965 study by the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority recommended even more dramatic expansion of the highway, including widening it from six lanes to ten lanes between the Lincoln Tunnel and West 59th St., crowding the adjacent buildings along most of midtown Mahattan’s Hudson River waterfront.

The West Side Highway needed an overhaul because it was corroded by salt used to melt snow and by pigeon excrement. In 1969, it was closed briefly when part of it collapsed, but it was quickly repaired.

Then on December 16, 1973, a cement truck going to make a repair on another part of the West Side Highway caused a 60 foot section of northbound roadway near Gansevoort St. to collapse. The highway was closed between the Battery and 57th St while engineers determined whether this section could be repaired.

In 1973, a sixty-foot stretch

of

the West Side Highway near

Gansevoort St. collapsed and

the

road was closed permanently.

Because the repairs were extimated to cost $88 million, the New York City Dept. of Transportation decided not to make them and instead diverted the highway’s traffic to a temporary route on West St. and Twelfth Ave. while the city decided how to replace the highway.

Demolition of the elevated structure began in 1977 but was not completed until 1989. During that time, the abandoned road became a popular place for jogging and bicycling, and concerts were held there.

The Westway Proposal

In 1969, as the Westside Highway began to deteriorate badly, New York city planner Samuel Ratensky proposed a new freeway further west, over the Hudson River.

In 1971, this new freeway was gained political support as part as a project known as “Wateredge,” which would include a new freeway and a transitway built on piles in the Hudson River. This project called for 700 acres of land to be created above the freeway, between the Battery and 72nd St, where there would be 85,000 new apartments and a park.

Both Governor Nelson Rockefeller and Mayor John Lindsay supported Wateredge and wanted to use federal interstate highway funding to construct it. This project gained momentum after the West Side Highway collapsed in 1973, and Planning Commission chair John Zuccotti gave it the name “Westway.”

But there was opposition to Westway, on the grounds that it would generate more traffic, waste money, and create environmental problems in the city and beyond. Opponents include Hugh Carey, a congressman from Brooklyn who was running for governor, and Edward Koch, a congressman representing a district in Greenwich Village who would later become mayor. Greenwich Village had been a center of opposition to Robert Moses projects, such as his attempt to route traffic through Washington Square Park, and it was also the center of much of the public opposition to Westway.

West St. at Gansevoort St.

today. It is easy for pedestrians

to

cross the

street between the city

and the waterfront.

The Environmental Impact Statement for Westway included six alternatives, and in March, 1975, Mayor Abe Beame and Governor Hugh Carey, who had opposed Westway when he was running for that office, announced their support for an alternative that would create 93 acres of landfill in the Hudson River and would build a new 4.2 mile freeway that tunneled under this land for much of its length and was elevated in some locations. The new land above the underground freeway would be used for housing, businesses, and parks.

In 1978, Edward Koch was elected mayor, and like Gov. Carey, he changed his earlier position and became a supported of Westway. The New York Times reported that support by these two Democratic leaders made Westway the “official” project for replacing the West Side Highway.

In August, 1981, the Army Corps of Engineers received a permit to do the dredging and landfill needed for Westway. At the same time, President Ronald Reagan announced his support for Westway, and at a public ceremony, presented city and state officials with an $85 million check to be used to start work on the project.

The Battle Over Westway

As mayors, governors, and a president lined up to support Westway, community boards, environmental groups, local politicians, and citizens opposed it.

Craig Whitaker, an architect who worked with city-planner Ratensky to develop the original plans for this freeway, presented the Westway plan to over 700 community meetings. He found that found that there was strong grassroots oppostion at these meetings, a continuation of New York’s freeway revolt.

During the 1960s, citizen opposition stopped many of Robert Moses’s freeway projects, including three proposed cross-Manhattan freeways, which would have torn up the city’s urban fabric by demolishing swaths of land a block wide to build freeways crossing Manhattan. Though he considered Westway a very different sort of project, he found that people at community meetings considered it a reincarnation of the cross-Manhattan expressways.

Opposition to Westway was led by Marcy Benstock, head of a group named the Clean Air Campaign. Benstock went to all the meetings where citizens were allowed to comment on the project and its environmental studies, patiently wrote down the names of all the people who spoke against the project, and organized these disparate individuals and groups into a movement cohesive enough to fight the project effectively.

After the Army Corps of Engineers got its permit in August 1981, the Clean Air Campaign and other groups sued. In 1982, Judge Judge Thomas Griesa of U.S. District Court stopped work on the project, on the grounds that the Corps of Engineers had not considered the impact of landfill on striped bass in the Hudson River. After threee more years, the Corps of Engineers produced a final study showing the the dredging and landfill would kill no more than one-third of the striped bass in the Hudson. But Judge Griesa said this study was inadequate and still refused to allow construction to begin.

Governor Mario Cuomo vowed to overturn this decision, but in September, 1985, New York City decided to abandon Westway.

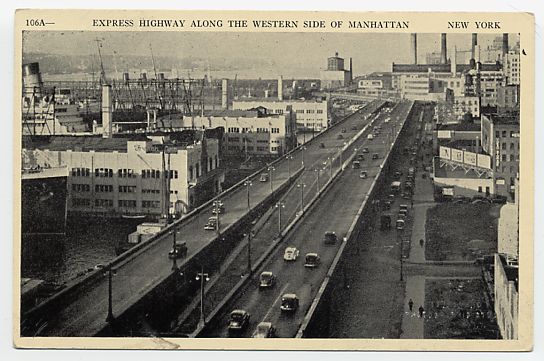

This postcard of

West Side Highway shows

how

the

elevated highway

overshadowed

the street.

Of the $1.7 Billion in federal highway funds that had been allocated to build Westway, the city shifted about 60% to improving mass transit. It shifted the other 40% of these funds, plus an additional $121 million of city and state funds, to the West Side Highway Replacement Project. This project was capped at $811 million, so it was only able to make modest improvements to existing roads and to create a new park along the river.

Benstock commented, “We were all told at the beginning, You can't stop this - the people who want Westway are too powerful.' Nevertheless, we fought, and it took 11 years, but in the end, we won.”

Why did the city abandon Westway? The environmental arguments were important. In addition, Benstock had cultivated allies among fiscally conservative congressmen and New Jersey legislators who were afraid that Westway would reduce their share of federal highway money, and these allies in Congress helped to redirect Westway’s funding to public transportation.

Just as important was the delay itself. In 1969 and 1973, everyone believed the city planners and traffic engineers who said that the Westside Highway had to be replaced to avoid gridlock. But in 1985, the city had survived for 12 years without this highway. After such a long time without a freeway, Westway looked less like a replacement and more like a new freeway project extending into Manhattan, which would generate more traffic as new freeways always do.

A Park Along the Hudson

In September, 1986, the city hired Volmer Associates to develop alternatives for the West Side Highway Replacement Project. Their four alternatives all involved improving the existing roadway and adding a park along the Hudson River, though one also included a depressed lane whose direction would be reversed to handle increased traffic.

In May, 1993, the city finally adopted alternative 3, which some community members called “Lessway” because its $380 million cost was so much less than the cost of earlier proposals. The project was completed in 2001, twenty-eight years after the West Side Highway collapsed and was closed permanently.

This project simply improved the existing West St., which had been the street under the elevated West Side Highway, by adding 19-foot wide landscaped medians, a bicycle path and landscaped park along the river, and urban design elements that emphasize the continuity of this street and park, such as decorative streetlights and granite paving details.

Most of this street is four lanes each way, but part has only three lanes southbound, and the stretch between 14th St. and 24th St. is only three lanes each way. At 57th St., it connects with a section of the original West Side Highway (or Miller Highway) viaduct, restored at a cost of $80 million, which leads to the Henry Hudson Parkway north of 72nd St.

Between 14th St. and

24th St., West St. is

only three

lanes in

each

direction, making

for a pedestrian-friendly street.

This bicycle path and park are part of the planned East Coast Greenway. They will ultimately connect with parks in Donald Trump’s expected Riverside South development below 72nd St, which will connect with Frederick Law Olmstead’s Riverside Park (extending from 72nd St. north), and ultimately with the planned Hudson River Valley Greenway extending to Albany.

Text copyright 2007 by the Preservation Institute

Photographs of current conditions copyright 2007 by Charles Siegel